The US Defense Department has confirmed that Boubaker al-Hakim, a French-Tunisian Islamic State leader pictured above, was killed in airstrikes carried out in Raqqa, Syria on Nov. 26.

In a statement on Dec. 10, Pentagon Press Secretary Peter Cook described al-Hakim as a “longtime terrorist with deep ties to French and Tunisian Jihadist elements.” Cook tied al-Hakim to the so-called caliphate’s external operations arm, saying his death “degrades” the Islamic State’s “ability to conduct further attacks in the West” and denies the group “a veteran extremist with extensive ties.”

Cook also noted that al-Hakim is “suspected of involvement” in terrorist attacks against “Tunisian political leadership” in 2013. Indeed, al-Hakim admitted in an interview with the Islamic State’s Dabiq magazine in early 2015 that he assassinated one Tunisian politician and knew the jihadists responsible for killing a second.

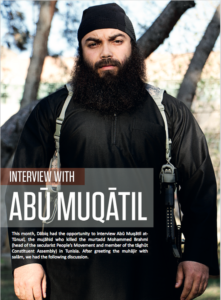

Interview with Dabiq

Al-Hakim was identified as Abū Muqātil at-Tūnusī in the 8th issue of Dabiq, which was released online in March 2015. He bragged about killing Mohammed Brahmi, the leader of the People’s Movement party, on July 25, 2013.

“We stayed four hours in front of the home of this tyrant, waiting, until he left the home and entered his car,” al-Hakim told Dabiq. “I then moved towards him and killed him by shooting ten bullets at him.”

“We wanted to cause chaos…in the lands by killing Brahmi so as to facilitate the brothers’ movements and so that we would be able to bring in weapons and liberate our brothers from prisons,” al-Hakim said, explaining the rationale behind Brahmi’s slaying. “This was the main goal behind killing Brahmi in addition to the fact that he worked in [Tunisia’s] Constituent Assembly making him from the tawāghīt [apostate rulers] of the country.”

Al-Hakim also identified three jihadists who were responsible for the assassination of another Tunisian politician, Chokri Belaid, on Feb. 6, 2013. One of them was known as Ahmad ar-Ruwaysī. According to al-Hakim, ar-Ruwaysī escaped from prison following the uprising in Tunisia in 2011 and fled to Libya, where he helped run a training camp and smuggle arms back into Tunisia. After Belaid was killed, ar-Ruwaysī became a wanted man and so he stayed in Libya. Al-Hakim told Dabiq that ar-Ruwaysī joined the Islamic State in Sirte, which was the group’s stronghold in North Africa from mid-2015 until earlier this year. It was in Sirte that ar-Ruwaysī swore allegiance to Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s operation before dying in battle.

His interview with Dabiq wasn’t the first time al-Hakim admitted a role in the assassinations of Brahmi and Belaid.

In Dec. 2014, the Islamic State released a video calling on Muslims to support the group’s jihad in Tunisia. Al-Hakim starred in the production.

“Yes, O tyrants, we are the ones who assassinated Chokri Belaid and Brahmi, and, Allah permitting, we will return,” al-Hakim said, according to a translation by the SITE Intelligence Group.

Al-Hakim announced his fealty to Abu Bakr al Baghdadi and encouraged Tunisians to pledge their own allegiance to the Islamic State’s master. He also threatened France. “We will tear apart that flag that was raised by the grandchildren of Charles de Gaulle” and “the grandchildren of Napoleon,” raising the black banner of monotheism in its place, al-Hakim said.

A veteran jihadist

Al-Hakim briefly recounted additional biographical details in his interview with Dabiq. He said that his “religious practice started in 2002” when he traveled “to Sham,” meaning the Levant (Syria), “to study the Sharia.” After the Americans entered Iraq in 2003, al-Hakim briefly joined the jihad there for “about a month” before being “betrayed by some of the hypocrites” and “forced to leave.”

Al-Hakim then went to France, where he “prepared for another journey” to Iraq. He joined Abu Musab al Zarqawi’s group. He met up with Zarqawi and his men in Fallujah, staying in the city for “about six or seven months.” Al-Hakim said he left Iraq for Syria “to receive my family,” but “was arrested there.” He was then imprisoned in Bashar al Assad’s notorious and controversial Far’ Falastin prison, which housed other well-known jihadists, “for nine months.” He was deported to France and “imprisoned there for seven years.”

Al-Hakim said his time in a French prison was “difficult,” but it was also “a great gate for da’wah [proselytization] to Allah” and a “school” for indoctrinating others in the jihadist ideology.

It appears that al-Hakim returned to Tunisia around the time of the Arab uprisings in 2011. “I then left back to Tunisia and started planning on establishing jihād in Tunisia with my brothers,” al-Hakim told Dabiq. “Libya was next to us and weapons were widespread there,” al-Hakim continued. “So we went to Libya and established a training camp there” and “would work to smuggle weapons into Tunisia.”

Al-Hakim portrayed the assassinations of Belaid and Brahmi as a strategic failure, admitting that the slayings did not spark a broader jihadi revolution. “The matter succeeded but some of those associated with jihād there, may Allah guide them, went out and defended the former government institutions and thereby ruined our mission,” al-Hakim told Dabiq. “After all these attempts I decided to go to Shām and join the Islamic State there.”

The French-Tunisian jihadist was also especially critical of the Islamists in Tunisia who failed to support the supposed caliphate’s cause. Al-Hakim called on Tunisia’s Islamists to “repent,” arguing that their “ideas” and participation in elections “have not brought you any results.” Only armed jihad was sufficient, from al-Hakim’s perspective.

In his interview with Dabiq, al-Hakim praised the March 18, 2015 attack on the Bardo National Museum. Dozens of people, mainly foreign tourists, were killed or wounded in the massacre. Al-Hakim said this “delighted us and healed our hearts,” adding that other “brothers” should carry out similar operations. CNN reported that he is also suspected of having connections to the jihadi gunman who killed 38 people at a tourist beach near Sousse, Tunisia on June 26, 2015.

Tied to Ansar al Sharia Tunisia, European jihadists

Al-Hakim was designated as a terrorist by both the United Nations and the US State Department in Sept. 2015. Both designations noted al-Hakim’s reported “ties” to Ansar al Sharia Tunisia, which orchestrated the Sept. 14, 2012 assault on the US Embassy in Tunis.

The designations noted that al-Hakim “worked with related associates to target Western diplomats in North Africa,” but didn’t specifically tie him to the ransacking of the American embassy. Just days earlier, Ansar al Sharia Libya was part of a coalition of al Qaeda groups that attacked and killed four Americans in Benghazi on Sept. 11, 2012.

The Tunisian government first reported al-Hakim’s connections with Ansar al Sharia Tunisia in 2013. Officials accused Ansar al Sharia’s leader, Seifallah Ben Hassine (also known as Abu Iyad al Tunisi), of ordering the hit on Belaid. Tunisian authorities also reported that a forensic investigation tied the killings of Belaid and Brahmi to the same jihadi network and even the same weapon. [See FDD’s Long War Journal reports: Tunisian government alleges longtime jihadist involved in assassinations and Ansar al Sharia responds to Tunisian government.]

After the Ansar al Sharia groups gained international infamy in 2012, many accounts sought to distance them from al Qaeda’s network. However, as The Long War Journal reported at the time, the Ansar al Sharia organizations in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen all had demonstrable ties to al Qaeda. The Long War Journal’s analysis was subsequently confirmed by the details reported in UN and American designations, as well as other evidence.

The rise of the Islamic State in 2013 and 2014 led some jihadists, such as al-Hakim, to defect to the self-declared caliphate’s cause. Others, including Ansar al Sharia Tunisia leader Hassine, remained loyal to the al Qaeda network. According to letters that were released via social media, Hassine initially urged Ayman al Zawahiri to join the Islamic State’s then surging effort. But Hassine quickly did an about-face, concluding that Baghdadi and his followers were too extreme even for al Qaeda. Some sources have reported that Hassine was killed in 2015, but his demise was never confirmed.

Al-Hakim and his comrades went all in for the Islamic State. In the Dec. 2014 video, he called on jihadists in Tunisia to defect to Baghdadi’s enterprise en masse. “I call on my brothers in Tunisia in general and my brothers in the mountains in particular to follow their brothers in Libya, Algeria, the Land of the Two Holy Mosques [Saudi Arabia], Yemen, and Sinai, and pledge allegiance to the Emir of the Believers,” al-Hakim said, according SITE’s translation. While some answered the call, others didn’t. For instance, the Uqba bin Nafi battalion in the Mount Chaambi region remained loyal to al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

The divide among al-Hakim’s jihadi friends extended all the way into Europe. When al-Hakim’s death was widely reported earlier this month, some accounts linked him to the mass murder at Charlie Hebdo’s offices in Paris in Jan. 2015. That operation was carried out by two brothers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi. It is likely that al-Hakim, who was born in Paris, knew one or both of the Kouachi brothers in France. Al-Hakim was a key figure in a recruiting cell based in the 19th Arrondisement of Paris. Al-Hakim’s network sent aspiring jihadists off to fight in Iraq and the Kouachis were tied to this same operation.

However, al-Hakim did not specifically mention the Charlie Hebdo attack in his interview with Dabiq, which was posted online more than two months after the fact. The Kouachis carried out the assault on behalf of al Qaeda and al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). A friend of the Kouachis, Amedy Coulibaly, murdered others in the name of the Islamic State. But the Kouachis did not follow Coulibaly into the caliphate’s camp. In reality, while their specific allegiances differed, they were all jihadis and knew each others years beforehand.

While al Qaeda is still capable of plotting a mass-casualty attack and celebrates indiscriminate killings in the West, the group has also experimented with more targeted slayings, such as the Charlie Hebdo operation. An AQAP analysis, for example, explained that al Qaeda’s central leadership had selected “particular target[s]” to strike.

Al-Hakim was less interested in this style of terror. In Dabiq, he called on jihadis in France to lash out. “I also say to them, do not look for specific targets,” al-Hakim stressed. “Kill anybody. All the kuffār [unbelievers] over there are targets. Don’t tire yourself and look for difficult targets. Kill whoever is over there from the kuffār.”