Yesterday (Feb. 9), the jihadi known as Abu Jaber released his first speech as the leader of the newly formed Hay’at Tahrir al Sham (HTS), or “Assembly for the Liberation of the Levant.”

In late January, al Qaeda’s branch in Syria, Jabhat Fath al Sham (formerly known as Al Nusrah Front), and four other groups announced the creation of HTS, with Abu Jaber as their leader. [See FDD’s Long War Journal report, Al Qaeda and allies announce ‘new entity’ in Syria.]

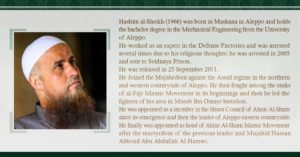

Abu Jaber (seen above) had been a prominent figure in another organization, Ahrar al Sham, which he led from Sept. 2014 to Sept. 2015. But he resigned from Ahrar entirely to become the “general commander” of HTS.

Abu Jaber begins his speech by mentioning the many “difficulties” the insurgents in Syria currently face, including “military, political, [and] civil” challenges. He says that HTS was formed “to safeguard the gains of the revolution and the land that was liberated” with the blood of thousands of “martyrs.”

He emphasizes that HTS “is an independent entity and not an extension of previous organizations or factions.” Instead, he claims, “it is a merger where all factions and titles were dissolved and disintegrated.” With these lines, Abu Jaber undoubtedly intends to distance HTS from the legacy of al Qaeda’s official arm, which he and others now argue no longer exits.

The creation of HTS “ushers in a new stage in the life of the blessed revolution” and seeks to unite the various insurgent groups under the banner of “one entity,” with a “unified leadership” that “will guide the political and military work of the Syrian revolution toward achieving its goal.” Their chief mission, Abu Jaber stresses, is to topple Bashar al Assad’s regime. And HTS will be begin its “military work” against the regime in short order. This “war of liberation” will “achieve great victories,” he promises.

Abu Jaber rallies his “brothers” in HTS, saying they are at “the forefront of the Syrian jihad” and stories of their “heroism and victories” have motivated the people. They have handed Assad’s regime defeats, “humiliated” Hezbollah, and faced down the Russians, Abu Jaber says. He calls on other factions to join HTS and also warns all Sunnis in Syria of the dire circumstances they would face should the war be lost. In that event, he claims, the Shiites (“rejectionists”) will “enslave the region.”

HTS was not established over night. It is the product of a long-running debate within the jihadi community over the best course for surviving and achieving victory in Syria.

Abu Jaber’s background

Abu Jaber (also known as Hashem al Sheikh) rose to prominence in Syria in Sept. 2014, when he was named the new emir of Ahrar al Sham. He continued in that role for one year before voluntarily stepping down in Sept. 2015. He was pressed into service after the first leader of the group, Hassan Abboud, was killed along with his comrades in a mysterious explosion. Abboud, who was a student of the famous al Qaeda leader known as Abu Khalid al Suri, was a popular figure among jihadis and Islamists in Syria. When Abboud and many of his closest advisors in Ahrar al Sham perished, Abu Jaber suddenly inherited a greatly weakened organization, at least at the leadership level.

Ahrar al Sham released a short biography for Abu Jaber on Sept. 10, 2014. It can be seen on the right. A native Syrian, he was “born in Maskana in Aleppo” and eventually received a bachelor’s “degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Aleppo.” Abu Jaber worked for a time “as an expert in the Defense Factories,” but he was “arrested several times due to his religious thoughts,” which is likely a reference to his Salafi-jihadist beliefs.

Bashar al Assad’s regime arrested Abu Jaber in 2005 and sent him to the notorious Sednaya Prison. He was held alongside other jihadis who would eventually be freed and then help lead the fight against the Syrian government. Abu Jaber was released from Sednaya on Sept. 25, 2011 and then “joined the Mujahideen against the Assad regime in the northern and western countryside of Aleppo.”

Abu Jaber “fought among the ranks of al-Fajr Islamic Movement” and later led others from “his area in [the] Musab Ibn Omayr battalion.” Abu Jaber’s men fought alongside the group formerly known as Al Nusrah Front, al Qaeda’s official Syrian branch.

Abu Jaber’s organization was folded into Ahrar al Sham and its joint venture, the Islamic Front. And he was eventually “appointed as a member” of Ahrar al Sham’s elite shura (or advisory) council, as well as the group’s “leader” in the eastern countryside of Aleppo.

It is possible that there were some intriguing details left out of Ahrar al Sham’s Sept. 2014 biography of Abu Jaber. Shortly after he was named as the head of HTS in late January, jihadis circulated another short dossier on him. A similar document was previously posted online by El-Dorar Al-Shamia. The events described in this version of Abu Jaber’s life are basically the same as in Ahrar al Sham’s biography, with two noteworthy additions.

First, according to this alternate biography, Abu Jaber joined the jihad in Iraq during the height of the war. He reportedly helped facilitate fighters through Syria and into Iraq. If accurate, then this implies that Abu Jaber was a facilitator for al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI). It is well known that Bashar al Assad’s regime hosted AQI’s major pipeline, which sent jihadis into Iraq to fight the Americans. Abu Jaber was imprisoned by the Assad regime from 2005 to 2011, but this doesn’t preclude the possibility that he worked for AQI’s network, as Assad’s security services periodically detained jihadis in order to maintain control over the operation. While Assad’s government imprisoned some Sunni jihadis, it allowed others to operate with relative impunity.

Second, it appears that Abu Jaber was named the head of Ahrar al Sham’s operations in Aleppo’s eastern countryside after Abu Khalid al Suri was killed in Feb. 2014. If this is true, then it is another especially important detail. Abu Khalid al Suri was one of the most senior figures in Ahrar al Sham, as well as Ayman al Zawahiri’s most trusted advisor in Syria. That Abu Jaber could succeed Abu Khalid as the chieftain for eastern Aleppo indicates that others in Ahrar al Sham already held him in high regard.

In Apr. 2015, Al Jazeera broadcast a lengthy interview with Abu Jaber. He complained about Al Nusrah Front’s role as a branch of al Qaeda. Abu Jaber argued that Al Nusrah’s allegiance to al Qaeda hurt the Syrian revolution. Other Ahrar al Sham commanders have made the same argument, claiming that al Qaeda’s overt presence in the rebellion hinders the effort to topple Assad by bringing unwanted scrutiny from the international community. These same Ahrar al Sham leaders likely realize that the nations opposed to Assad will not provide as much assistance as they could as long as al Qaeda, an international pariah, is recognized as a strong player on the battlefield.

Abu Jaber’s critique was not a disavowal of al Qaeda; it was a common sense observation.

Indeed, al Qaeda’s own senior leaders tried to hide their affiliation with Al Nusrah Front at first for precisely this reason. Al Qaeda wanted to avoid the unwanted attention that comes with the al Qaeda brand name as it built up its paramilitary army and focused on toppling Assad. As a result of an open dispute with the Islamic State’s Abu Bakr al Baghdadi in Apr. 2013, however, Al Nusrah Front leader Abu Muhammad al Julani revealed his allegiance to Ayman al Zawahiri. The al Qaeda chieftain criticized Julani’s decision, noting that al Qaeda had not given him permission to announce his fealty or reveal his connections.

Al Qaeda even embedded veteran operatives in Ahrar al Sham’s ranks, with the intent of clandestinely guiding the group. Men such as Abu Khalid al Suri, Abu Hafs al Masri, and Abu Hani al Masri had well-documented al Qaeda pedigrees, which were not advertised to the public even as they helped lead Ahrar al Sham’s operations.

For years, Ahrar al Sham and al Qaeda’s arm in Syria (rebranded as Jabhat Fath al Sham in July 2016) have been close battlefield partners. The two organizations established a series of coalitions throughout 2015, including during Abu Jaber’s tenure as Ahrar al Sham’s overall commander. The most successful of these was Jaysh al Fateh, which overran Assad’s forces in the province of Idlib in early 2015. In May of that year, while Abu Jaber was still Ahrar’s overall leader, they also jointly created Ansar al Sharia in Aleppo. This military alliance quickly became defunct, but it was an attempt to unite various jihadist, Islamist and other factions. [For more on Ansar al Sharia and the jihadists’ other coalitions throughout Syria, see FDD’s Long War Journal report: Al Nusrah Front, allies form new coalition for battle in Aleppo.]

Abu Jaber has eulogized fallen jihadists, including members of al Qaeda’s branch, as “martyrs” on his Twitter feed. In one tweet on Feb. 26, 2015, for instance, he asked Allah to “comfort our dear brothers in the #Al Nusrah Front regarding” three slain fighters, including one who was the “emir of the Syrian Desert.” In early Jan. 2016, Abu Jaber honored a deceased Ahrar al Sham commander known as Abu Rateb al Homsi, whom Al Nusrah Front identified in its own eulogy as a jihadist who had fought in Afghanistan.

During Abu Jaber’s time as Ahrar al Sham’s emir, the group also openly praised the Taliban and its deceased leader Mullah Omar for showing jihadists “how to build the [Islamic] Emirate in the hearts of the people before it becomes a reality on the ground.”

It is a goal that Abu Jaber has apparently taken to heart.

Abu Jaber: “The jihad must be a popular jihad.”

Jihadism has been evolving for some time, but especially since 2011, when uprisings throughout the Arab world shook the dictatorships that had long maintained a stranglehold on their societies. The revolutions presented a new opportunity for jihadists to spread their ideas and attempt to win popular support. Suddenly, there was a range of options open to the jihadists.

On one end of the spectrum was Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s top-down, authoritarian Islamic State, which rejects compromise, even with its closest ideological cousins. Prominent jihadi thinkers, including within al Qaeda, have long considered Baghdadi’s approach to be a long-term loser, as it alienates much of the Muslim population and invites outside parties (especially the US) to intervene. Al Qaeda’s leaders rejected the Islamic State, in part, because they feared that Baghdadi’s men would spoil the jihad in Syria. Most Muslims in Syria and elsewhere do not pine for Islamic State-style rule.

Al Qaeda shares many of the same goals as Baghdadi and his enterprise, but has adopted a radically different strategy for achieving them. In many ways, the war in Syria brought the jihadis into unchartered waters, as they are attempting to achieve a lasting victory without resorting to Baghdadi’s immediate totalitarianism. It is a difficult balancing act, as there are undoubtedly many jihadis within al Qaeda’s sphere of influence who want to immediately impose a Draconian-style of sharia similar to the Islamic State’s laws. The lure of declaring an Islamic emirate in northwestern Syria has also been strong, even though al Qaeda thinks it would be premature. Should the jihadis and Islamists in Idlib announce that they now control a Taliban-style state, and then lose control over it, the very notion of an Islamic emirate could be discredited in the people’s eyes.

Ahrar al Sham, including during Abu Jaber’s one-year tenure, has attempted to navigate these difficult waters. There is not one settled school of practical thought for them to follow. So, there have been regular disagreements over how much the jihadis should be tactically flexible. Some have sought to portray Ahrar al Sham’s quest for a practical jihadism as distinct from al Qaeda’s own experimentation, but this is not the case. It is evident to any careful observer that al Qaeda itself has been debating, sometimes in vitriolic terms, which path is best for achieving its goals without abandoning or severely compromising on its Salafi-jihadist ideology. Al Qaeda’s own official arm in Syria, first known as Al Nusrah Front, then as Jabhat Fath al Sham, has embodied different ideas. One al Qaeda theorist has even advocated that the jihadis adopt “political guerrilla warfare,” such that it enhances their “resilience” in the face of militarily superior Western foes. Indeed, the Afghan Taliban, which remains closely allied with al Qaeda to this day, has long mixed its own form of politics with jihad.

Abu Jaber is clearly aware of this evolution in the jihadis’ thinking. He has lived it. And he has moved himself to the forefront of the quest to develop a practical program that would allow the jihadis to survive and thrive in Syria.

In 2016, Al Jazeera produced a lengthy documentary on Ahrar al Sham that highlighted how Salafi-jihadists were adapting to events on the ground in Syria.

Ahrar’s first emir, Hassan Abboud, traced this evolution to the time he and others, including Abu Jaber, spent in the Sednaya Prison. The prisoners represented different camps within the Islamist and jihadist worldview. While they shared many points in common, they also had significant differences. “The Sednaya prison phase, to be honest, during it, some of the concepts and visions were rectified and for the first time, we lived the difference between theory and practice, when you follow the path of Jihad, especially the Salafi-jihadist [ideology],” Abboud said.

For his part, Abu Jaber said he rejects any ideologue who is quick to “label” others just because he doesn’t agree with him on every detail. “There are people who, I mean, just for having a different opinion from them, they have labels which [they] label you with, and name you with the names which they choose,” Abu Jaber said. “People of ignorance we call them. They don’t want to learn. The only thing they understand about religion is to sacrifice their blood, to die, and only that.”

Abu Jaber wants more than that. He wants to transform Syrian society.

“We didn’t want the Islam of caves” or the “Islam of rifles,” Abu Jaber told Al Jazeera. “The Islam, the right understanding of it, is that it is a religion, a country. It’s politics and it is fighting. It’s ruling and it’s knowledge.”

The Al Jazeera documentary did a good job of explaining why this has been difficult for the jihadis to achieve. Al Jazeera’s journalists used the example of Aleppo, where “mixed ideologies” have existed. Along with Al Nusrah Front and Liwa al Tawhid, Ahrar al Sham established the city’s “first judicial body.” But this ruling religious authority immediately encountered problems. Islamists and more secular parts of the society disagreed over how to govern. Ahrar al Sham’s leaders explained these problems in the documentary, emphasizing that it is difficult to establish a truly competent administrative body in a revolutionary environment in which the war is far from over. In one clip, an Ahrar al Sham leader implores his audience to stop protesting against the religious committee and to work out their differences instead. Clearly, this early attempt at jihadi governance in Syria was a failure.

“Everyone agrees that there were mistakes,” Abu Jaber said of the attempt to rule in Aleppo. “We have to learn from those mistakes, so we don’t fall for them again. The solution is not to rely on the Jihad (opinion) of the elite. The Jihad must be a popular jihad.”

In other words, the jihadists can be successful only once their ideology has been adopted by a significant portion of the population. Another Ahrar leader went even further than Abu Jaber, saying that “the followers of the Salafi-jihadist ideology have tarnished themselves by claiming their jihad to be the jihad of the elite.”

In contrast to the Islamic State’s top-down authoritarianism then, Ahrar al Sham figures such as Abu Jaber have adopted a bottom-up approach, seeking to spread their beliefs so that their state-building project cannot be easily uprooted. The problems they have encountered are numerous. Some of their own members haven’t understood how their ideology differs from the Islamic State’s and, at times, even refused to fight Baghdadi’s men as they marauded their way through parts of Syria.

“Many of the brothers dropped their weapons and left,” Abu Jaber told Al Jazeera, referring to the early days of the conflict with Baghdadi’s so-called caliphate. They “dropped their weapons and left, to avoid the spilling of Muslim blood.” Abu Jaber explained why: “The surprise was that there was no prior intellectual foundation.” Abu Jaber likely meant that, in the beginning, Ahrar al Sham’s own foundation was shallow and his comrades lacked a deep cadre of support from which they could draw in the battle against Baghdadi’s adherents.

Al Qaeda’s branch in Syria (most recently known as Jabhat Fath al Sham), Ahrar al Sham and other organizations have spent years cultivating more popular support for their project. They are far beyond square one, but still well short of their ultimate goal: a new Islamic emirate in Syria.

A “new path”

Muhannad al Masri succeeded Abu Jaber as the head of Ahrar al Sham in Sept. 2015. In his own interview with Al Jazeera the following year, al Masri praised Abu Jaber’s stewardship of the group, saying it “started following the institutional and administrative methodology excellently” during his tenure. “Sheikh Abu Jaber was quite devoted to it at the end of the year when he was in charge,” al Masri explained. But Abu Jaber “resigned from the Shura [council] of Ahrar al Sham, so he could go down a new path in the world of Islamic and Jihadi movements.”

Muhannad al Masri didn’t explain what this “new path” entailed, but Abu Jaber has been positioning himself for another leadership role for some time.

In Feb. 2016, several reports suggested that Abu Jaber was going to lead a new joint venture of several parties in Aleppo. The alliance didn’t get off the ground, but the effort demonstrated that Abu Jaber was considered someone capable of uniting various factions under a single banner. [See FDD’s Long War Journal report, Aleppo-based rebel groups reportedly unite behind Ahrar al Sham’s former top leader.]

Then, in late 2016, Abu Jaber and other senior Ahrar al Sham figures formed their own internal contingent named Jaysh al Ahrar. Although they didn’t break away from the Ahrar al Sham mother organization at the time, the creation of Jaysh al Ahrar clearly signaled that there was an internal divide.

Those divisions became obvious earlier this year. Ahrar al Sham has split into different factions, with Abu Jaber and other founding members joining HTS. According to pro-HTS accounts, a large number of Ahrar’s battalions have joined them. Meanwhile, other leaders continue to run the original organization, absorbing smaller groups in the process.

It says much about Abu Jaber’s influence and the respect al Qaeda’s jihadis have for him that they accepted him as the first leader of HTS. Abu Muhammad al Julani, the longtime emir of Al Nusrah/Jabhat Fath al Sham, stepped aside to allow Abu Jaber to fill the top spot. As the miltary commander of HTS, Julani still wields considerable power within the organization. But Abu Jaber is its front man. The new flag for HTS can be seen on the right.

The formation of HTS came at a time when al Qaeda’s men in Syria feared that their enemies were launching a new conspiracy against them. By merging with other groups and embedding their operations within HTS, al Qaeda clearly hopes to minimize additional international attention.

In January, representatives from some Syrian opposition groups traveled to Astana, Kazakhstan for diplomatic talks. Jabhat Fath al Sham’s members portrayed the negotiations as part of a plan to turn other insurgents against them. Tellingly, HTS staged rallies in which Abu Jaber was praised for rejecting the talks. Some of the signs that were held up (seen below) praised Abu Jaber while denouncing Jaysh al Islam’s Mohammad Alloush, who served as one of the rebels’ chief negotiators.

Abu Jaber and his newly formed HTS are now charged with defending the jihadist project in Syria. And his “new path” incorporates the group first known as Al Nusrah Front and then as Jabhat Fath al Sham — which is al Qaeda’s largest branch in history.

In early February, pro-HTS Telegram channels posted the pictures below of protests in Syria. Abu Jaber was praised for rejecting the talks in Astana, while Alloush was denounced for taking part in them:

Note: Jihadi media outfits, including Bilad al Sham, have produced multiple translations of Abu Jaber’s speech.

1 Comment

minor point: mostly you call them “jihadists” but sometimes “jihadis”, the ideology is treated analogously. Is there a deeper meaning to this or is that the result of different people contributing to this (excellent) report/analysis?