This article offers a preliminary analysis of the Battle of Avdiivka, particularly its final weeks. While more information will no doubt come to light as time passes, some initial conclusions stand out. Overall, the battle was favorable for Ukraine in that it sapped a large amount of Russian combat power. But once the city’s fall became inevitable, Ukraine’s withdrawal commenced too late. Ukraine also failed to adequately prepare a secondary line of defense behind Avdiivka. Still, Russia will likely be unable to make major additional gains in the area, at least in the near term.

Background: Russia’s Monthslong Offensive at Avdiivka

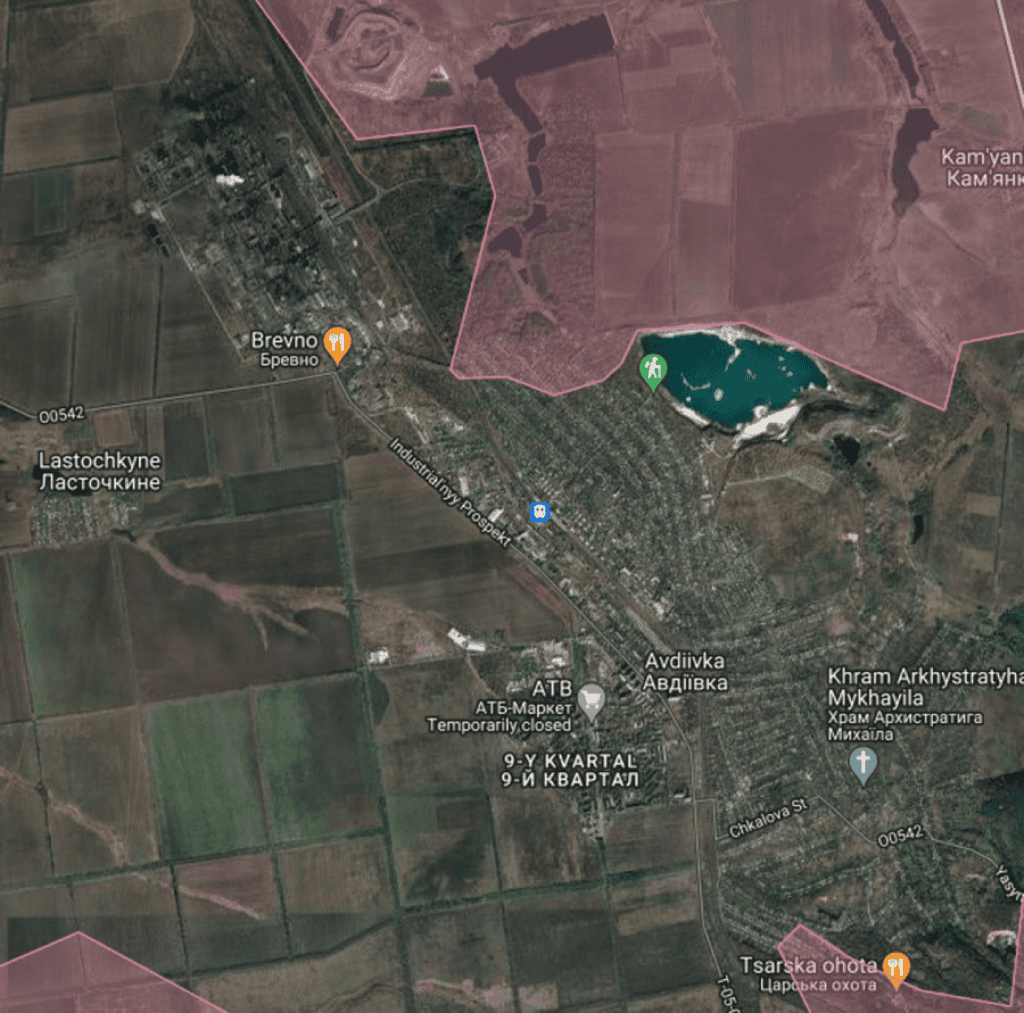

A small city located near Donetsk, Avdiivka had been on the front line for nearly a decade. By fall 2023, it was already semi-encircled. Moscow launched its most recent offensive in October, aiming to envelop Avdiivka from the north and southwest.

Russia devoted a sizable force to the operation. It consisted mainly of units from the 1st Army Corps and from Central Military District (CMD) brigades that had recently redeployed to the Avdiivka area. The initial attack comprised mechanized infantry and armor units totaling perhaps a regiment in strength — far larger than the company- or platoon-sized assaults on which both sides have come to rely. In the subsequent days, Russia continued to feed additional units into the offensive. Artillery and aviation provided support, although Russia probably struggled to synchronize between combat arms.

Facing a prepared Ukrainian defense, Russia’s initial attacks yielded little more than heavy losses. Ukrainian drone reconnaissance could quickly spot Russian columns as they advanced through fields. Ukrainian mines, first-person view (FPV) attack drones, anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs), and artillery fire chewed up the attacking forces. Russian observers complained of insufficient counter-battery fire and poor coordination between units, manned largely by hastily trained personnel.

To shore up Avdiivka’s defense, Ukraine transferred additional forces to the area. They included the 47th Mechanized Brigade, equipped with Western-supplied Bradley infantry fighting vehicles and Leopard tanks. The 47th Brigade redeployed from Zaporizhzhia Oblast to Avdiivka’s northern flank in October despite having had little time to recover from significant losses suffered during Ukraine’s unsuccessful 2023 counteroffensive.

After its initial attacks failed, Russia reverted to inching forward using small assault groups. (This shift echoed a similar Ukrainian adaptation during Kyiv’s recent counteroffensive.) The Russians took a large slag heap near Avdiivka later in October, gaining important high ground at the city’s northern edge.

Russian forces eventually began attempting to penetrate the city itself. They achieved minor gains in southern Avdiivka in November, December, and January. In the latter case, 150 troops from Russia’s 60th “Veterans” Sabotage-Assault Brigade reportedly used an underground pipe to infiltrate to the rear of Ukrainian forces at the “Tsars’ka Okhota” fortified restaurant complex, although Ukraine ultimately contained the breakthrough. Meanwhile, in January, Russia also crept forward on Avdiivka’s northern outskirts.

Russia’s modest gains came at the cost of enormous losses, including hundreds of vehicles and many thousands of troops. Its equipment losses would eventually force Russia to transfer in some vehicles from its 25th Combined Arms Army, fighting in the area near Lyman to the northeast.

At the same time, Ukraine also ran increasingly low on men and ammunition. Kyiv’s troops grew exhausted due to lack of rotation, while Russia threw in more and more reserves. (According to Ukrainian military officials, Russia had around 40,000 to 50,000 troops in the Avdiivka area.) Russia enjoyed a considerable quantitative advantage in artillery, while shell hunger hamstrung Ukraine’s counter-battery fire and defense against assaults. Heavy Russian artillery fire and bombing gradually reduced Ukrainian defensive positions.

Russian Breakthrough

Russian bombing reportedly intensified in January. Moscow’s “UMPK,” an add-on kit that turns dumb bombs into guided glide bombs that can be launched from standoff range, enabled the Russian Air Force to play a greater role than it could earlier in the war. While often inaccurate, the UMPK allowed Russia to pound static targets. Russia reportedly dropped dozens of bombs on Avdiivka per day. Ukrainian troops later described Russian bombing as a key factor behind the city’s fall. The continual bombardment took a toll on morale, with most troops in Avdiivka suffering concussions, Ukrainian soldiers recounted.

In early February, Russian forces broke into Avdiivka from the north, through the “Ivushka” garden community. They thus bypassed the Avdiivka Coke and Chemical Plant, the key defensive stronghold at the city’s northwestern end. Ukrainian reports said the Russians exploited fog, which impedes unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) operations.

The Russians pushed toward the 00542 road and Industrial Avenue. The 00542 was Ukraine’s main supply route — and only paved road — into Avdiivka. It feeds into Industrial Avenue, which connects the coke plant to the “9th Quarter” high-rise microdistrict in southwestern Avdiivka. The 9th Quarter’s tall buildings provide a dominant height for conducting surveillance and drone and ATGM strikes. The 9th Quarter also sits next to the Avdiivka-Sjeverne road, Ukraine’s secondary ground line of communication to the city.

The breakthrough and the pace of Russia’s subsequent advance appeared to catch Ukraine off-guard. By February 5, Russian forces had reportedly pressed to within roughly a kilometer from the mouth of the 00542 road.

Reports vary as to which Russian units led the attack. According to some Russian and Ukrainian sources, elements of the 114th Motor Rifle Brigade (1st Army Corps), reinforced by units from the 80th Tank Regiment (90th Tank Division, CMD) and 30th Motor Rifle Brigade (2nd Combined Arms Army, CMD), executed the main effort.

However, other Russian and Ukrainian reports give different accounts. According to prominent Russian blogger Boris Rozhin, elements of the 74th Motor Rifle Brigade (41st CAA, CMD), supported by 114th Brigade units, were the first to enter Avdiivka. He said these forces were tasked with severing the 00542 road and allowing troops from the 35th, 55th, 15th, and 30th motor rifle brigades (41st and 2nd CAAs, CMD) to enter battle, which they allegedly did by the end of February 9. (A Ukrainian unit fighting in Avdiivka later said Russia had indeed deployed forces from those six brigades plus the 2nd CAA’s 21st Motor Rifle Brigade.) Meanwhile, Rozhin said, Russian assault groups also attacked Avdiivka from the northeast and south.

Ukraine Deploys Reinforcements

Kyiv scrambled to deploy reinforcements, most notably the elite 3rd Assault Brigade, led by the former commander of the Azov Regiment. One 3rd Brigade officer later asserted that the reinforcements were tasked with containing Russia’s advance to enable the withdrawal of other Ukrainian units. However, another Ukrainian military source told the Long War Journal that he believed the Ukrainian command initially aimed to reverse Russia’s gains and hold Avdiivka. Ukrainian journalist Yuriy Butusov reported the same. Regardless, by this point, Avdiivka’s fall was likely inevitable, as the 3rd Brigade officer noted.

When it deployed to Avdiivka, the 3rd Assault Brigade had been in the middle of replenishing its ranks and equipment after tough fighting in the Bakhmut area. Many of the 3rd Brigade troops who fought in Avdiivka had not seen combat before. Two officers from the brigade lamented that its already difficult task was made harder by a lack of well-prepared defensive positions within the city. Ukrainian troops recounted having to defend positions that were already lost or destroyed. Ukrainian soldiers also say they were heavily outnumbered. Still, Kyiv’s forces likely continued to inflict significant losses.

Video footage confirms that elements of the 3rd Assault Brigade had entered battle by February 13. However, its deputy commander later indicated that 3rd Brigade troops had arrived as early as February 4. Butusov similarly reported that the 3rd Brigade deployed to the Avdiivka area on February 3 and entered battle on February 6. The commander of the brigade’s 2nd Assault Battalion indicated his troops fought in the city for “nine days,” meaning they arrived on February 8 or 9. The commander of that battalion’s “NC 13” platoon said his men stayed in Avdiivka for “seven days.” A 3rd Brigade medic similarly said her unit (the 3rd Assault Company) arrived in Avdiivka on February 10.

Meanwhile, Ukraine withdrew some exhausted units from the 110th Mechanized Brigade, a press officer said on February 13. Since the 110th’s formation nearly two years prior, it had served as the backbone of Avdiivka’s defense, reportedly without rotation. A Ukrainian soldier later said the resultant exhaustion had led 110th Brigade troops to abandon their positions “without prior coordination.”

Russia Pushes Deeper Into Avdiivka

Russian forces continued to push past the railway that runs through Avdiivka. By February 13, they had reportedly severed Industrial Avenue after capturing the “Avtobaza” facility near that road. The Russians were soon threatening Lastochkyne, a small village just west of the city. Assault units from Russia’s 30th Brigade were the first to reach Industrial Avenue, soldiers from the brigade later claimed. By the afternoon of February 15, Russian forces, reportedly from the 30th and 114th brigades, had reached the intersection between the 00542 road and Industrial Avenue and taken the nearby “Brevno” restaurant complex.

Ukrainian accounts and video footage indicate BMPs (infantry fighting vehicles) and tanks supported Russian assault infantry inside Avdiivka. Russian spetsnaz (elite infantry) and SSO (special operations forces), equipped with night-vision devices, reportedly conducted nighttime assaults and sabotage operations and directed artillery fire and airstrikes. UAV crews from various units also directed artillery fire and bomb strikes and targeted Ukrainian forces using FPV drones.

Meanwhile, Russia was also advancing around “Zenit,” an old air defense base that served as a key defensive stronghold south of Avdiivka. On or around February 11, Russian forces reportedly began advancing near Opytne, a village southwest of Avdiivka. They were threatening to encircle Zenit by linking up with the Russian troops consolidated at Avdiivka’s southwestern edge. From there, they likely aimed to reach the 9th Quarter and cut the Avdiivka-Sjeverne road.

Late Withdrawal

Withdraw operations are highly challenging. If not carefully orchestrated, they can result in heavy casualties. Ukraine’s withdrawal from Avdiivka took too long to commence and at times seems to have been poorly coordinated. As some Ukrainian soldiers pointed out, the delay echoed Kyiv’s previous decisions to cling to nearly encircled cities — most notably Bakhmut — well after doing so became unwise.

Despite the growing risk of encirclement, Ukraine apparently held onto its easternmost position within the Avdiivka pocket, the Donetsk Filtration Station, for a remarkably long time. Information from Russian and Ukrainian sources indicates Ukrainian troops likely began withdrawing from the station on February 15. Russian forces, reportedly from the “Pyatnashka” and “Viking” units (1st Army Corps), took the station by the morning of February 16.

The delay’s consequences were perhaps most acute at Zenit. According to a soldier from a 110th Brigade company that defended Zenit, by January Ukrainian troops had to ration small-arms ammunition, food, and water. At around 9 PM on February 13, the soldiers were reportedly told to retreat “on their own.” Ukraine’s 53rd Mechanized Brigade was responsible for covering the withdrawal from Zenit, the brigade later said.

Small groups of 110th Brigade troops began leaving for Avdiivka on foot, but many were killed or wounded on the way there, according to soldiers from the brigade. The 110th said the withdrawal occurred amid “continuous bombardment by enemy aircraft and artillery, constant attacks by FPV drones, attacks on evacuation vehicles, and shelling of evacuation routes.”

Some of the troops at Zenit stayed behind to hold off the Russians and enable the evacuation of six wounded comrades. But on the morning of February 15, they were told evacuation vehicles could not reach their position. The troops were forced to abandon the wounded, narrowly escaping Zenit through a corridor that was reportedly just 120 meters wide. They then had to flee westward on foot to the villages of Sjeverne and Tonen’ke. By that point, Russia had rendered the 00542 road unusable, attacking anything that passed with artillery and tank fire, a 110th Brigade spokesman confirmed. (Troops from Russia’s 114th Brigade raised a flag on the famous sign on the 00542 by February 16.)

Infantrymen from Russia’s 1st “Slavic” Motor Rifle Brigade (1st Army Corps) took Zenit by the afternoon of February 15. Some of the wounded Ukrainian soldiers left behind at Zenit were later seen dead in Russian-released footage. The Ukrainians allege they were shot.

That same day, 1st Brigade forces also took the “Cheburashka” and “Vinogradniki-2” areas on Avdiivka’s southwestern outskirts. According to Russian sources, Russian troops reached Vinogradniki-2 using the same pipe previously used to infiltrate to the Tsars’ka Okhota area. Troops from the “Veterans” Brigade participated in the assault on southwestern Avdiivka. Elements of that brigade, along with forces from the 1487th Motor Rifle Regiment, 87th Rifle Regiment, and 10th Tank Regiment, reportedly continued to attack in southern and southeastern Avdiivka.

Withdrawing in Small Groups

Accounts from Ukrainian soldiers, along with video footage that began emerging on social media by February 16, indicate Ukrainian troops withdrew from Avdiivka itself in small groups over multiple days, often on foot. Because Russia had fire control over the 00542 road, the Ukrainians relied mainly on dirt roads. Retreating Ukrainian troops had to brave Russian artillery, bombs, and one-way attack drones. A unit from Ukraine’s 3rd Assault Brigade later said a “large number” of vehicles were “lost and damaged” during the withdrawal.

As Ukrainian troops withdrew, Russian forces pushed deeper into the city. Troops from Russia’s 55th Brigade reached the park in central Avdiivka by February 16. According to the Russian Defense Ministry, they pushed toward the city’s center via Soborna Street. Meanwhile, troops from Russia’s 74th Brigade progressed through the residential and industrial areas near the quarry on Avdiivka’s northeastern outskirts.

At this point, Ukrainian forces still held the coke plant, which reportedly housed around 1,000 troops. Ukraine reportedly also retained control of the area between the rail station and Turhenjeva Street in southwestern Avdiivka, providing a corridor through which to withdraw toward Sjeverne. Elements of Russia’s 30th Brigade were allegedly attacking southward to try to block the Avdiivka-Sjeverne road.

Colonel-General Oleksandr Syrskyi, Ukraine’s newly installed commander-in-chief, officially announced the withdrawal shortly before 1 AM on February 17. Syrskyi said he had ordered Ukrainian units to leave the city “in order to avoid encirclement.” A Ukrainian military spokesman later said the withdrawal was completed on February 17.

Ukraine’s 47th Mechanized Brigade said troops from its 25th Assault Battalion were the last to leave the coke plant. Soldiers from the 3rd Assault Brigade’s 2nd Assault Battalion, responsible for holding Ukraine’s left flank, withdrew “next to last,” its commander said. The 3rd Brigade reportedly received its withdrawal order on February 16 and had largely evacuated the coke plant by 5 AM the next day. Ukrainian troops claimed no one was left behind at the plant and the withdrawal from the facility proceeded in a hasty but orderly manner. 3rd Brigade officers said some of the brigade’s units were at times encircled but managed to break out.

According to Ukraine’s military intelligence directorate (HUR), troops from the 3rd and 110th brigades, HUR and SSO units, the State Border Guard Service’s “Dozor” unit, and the 225th Separate Assault Battalion held the evacuation corridor while the main force withdrew. Ukraine’s 53rd Brigade said it held the 9th Quarter. 53rd Brigade troops withdrew shortly after dawn on February 17, just before Russia took control of the Avdiivka-Sjeverne road. Some Ukrainian servicemen claimed Ukrainian artillery provided good cover for the withdrawal.

In many cases, Ukrainian troops appear to have hurriedly abandoned their positions, leaving behind things such as anti-tank weapons, ammunition, grenades, and Starlink terminals. In some (perhaps most) cases, higher echelons did coordinate the retreats using radio communications and drones. But some soldiers reportedly did not receive formal withdrawal orders and simply retreated on their own accord to avoid destruction or capture.

According to The New York Times, Ukrainian soldiers said some units retreated before others were aware the withdrawal had begun, putting them at risk of encirclement. The soldiers reportedly said communication issues, stemming from incompatible radio equipment operated by different Ukrainian units, led troops to be captured, wounded, or killed. Russian electronic warfare may have also played a role. According to a 3rd Brigade officer, Russian jamming made it difficult for Ukrainian units to communicate with higher echelons during the last several days of Avdiivka’s defense.

Russia Completes Capture of Avdiivka

Later on February 17, troops from Russia’s 114th Brigade raised a flag at the Avdiivka coke plant, while 35th Brigade soldiers occupied the Avdiivka rail station. Troops from Russia’s 239th Tank Regiment (90th Tank Division, CMD), 24th Spetsnaz Brigade, and 35th Brigade reached the Avdiivka city administration building, near the 9th Quarter. Russian soldiers raised a flag at the 9th Quarter’s southern end that same day.

74th Brigade troops operated in northeastern Avdiivka (reportedly along Pervomaiska Street) and raised a flag as far south as Mira Street. Gunfire could be heard in footage shared by 74th Brigade soldiers on February 17, indicating some Ukrainian troops may have still been in the city at that time. Similarly, Pyatnashka soldiers claimed (without providing evidence) that they encountered Ukrainian troops in Avdiivka on February 17.

The withdrawal was a perilous moment for Ukraine. If the bulk of Kyiv’s forces in Avdiivka were encircled and destroyed or captured, it would sap morale and facilitate further Russian gains west of the city.

On February 18, the commander of Ukraine’s “Tavria” Operational-Strategic Grouping of Troops, whose aera of responsibility includes Avdiivka, admitted that “a certain number of Ukrainian soldiers were captured” during the withdrawal’s “final stage.” A platoon commander from the 53rd Brigade said that while everyone from his battalion managed to escape, some Ukrainian troops “did get stuck.” He said his platoon had planned to return but was later ordered not to do so. The withdrawal “was planned very badly” if it was planned at all, he opined.

Exactly how many Ukrainians were captured remains unclear, however. Estimates vary. At the high end, a February 20 New York Times report cited two Ukrainian soldiers who estimated that 850 to 1,000 troops were captured or missing. This would have constituted a very large portion (perhaps even a majority) of Ukraine’s force inside Avdiivka during the city’s final defense. But while unnamed Western officials said that range seemed correct, available evidence suggests the true figure was much lower.

The estimate provided to The Times exceeds even the (likely inflated) figures touted by Colonel-General Andrei Mordvichev, the Russian commander responsible for Avdiivka. On February 24, he claimed that roughly 200 Ukrainian troops had surrendered during the clearing of Avdiivka and another 100 were expected in the coming days. U.S. officials told The Washington Post that Ukrainian officials had privately estimated that around 100 soldiers were captured. This estimate tracks with the number of purported Ukrainian prisoners seen in Russian-released videos reviewed by the Long War Journal.

On balance, it appears the bulk of the Ukrainian force in Avdiivka escaped the pocket, even if the withdrawal was less than orderly at times.

Aftermath of Avdiivka’s Fall

During the monthslong battle for Avdiivka, Ukraine failed to construct a solid second line of defense behind the city. This left Ukrainian troops in a tough spot once Avdiivka fell, forcing them to dig in and lay mines amid active fighting.

Russia has since managed to capture a handful of low-lying villages west of Avdiivka through attritional attacks by small assault groups. Moscow likely hopes its forces can reach the city of Pokrovsk, an important logistical hub in Donetsk Oblast. Pokrovsk is around 40 kilometers from Avdiivka as the crow flies.

Meanwhile, to the southwest, Russian forces are attacking near the towns of Marinka and Krasnohorivka, forcing Ukraine’s 3rd Assault Brigade to quickly redeploy two companies to the latter. Russia reportedly also transferred its 10th Tank Regiment to Novomykhailivka to try to help the 155th Naval Infantry Brigade finish taking that village.

However, Russia likely will not manage to make large-scale gains, at least in the near term. Russian momentum has slowed, and the bodies of water west of Avdiivka can serve as natural barriers. In addition, a new Czech-led initiative to secure 800,000 artillery shells for Kyiv should help alleviate Ukraine’s shell hunger. So will the eventual passage of the U.S. supplemental assistance bill, expected in April.

Furthermore, Russia has so far proven unable to rebuild force quality. As such, the Russians will likely continue to struggle to scale offensive operations. Moscow’s initial attacks at Avdiivka provide a good example. Russia will thus have to continue attempting to inch forward through small-scale assaults, suffering heavy losses in the process.

This will give Ukraine more time to build fortifications near Avdiivka and elsewhere, which the Ukrainians have finally begun doing in earnest. And over the long run, Russia cannot sustain such a high rate of losses.