On May 1, the US Department of Defense (DoD) released its latest semi-annual report on security and stability in Afghanistan. The report documents significant progress in both developing the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and in degrading the Taliban insurgency. A thorough analysis also requires an evaluation of risk, however. While there is progress to report, it is important to note that there are also high, and increasing, risks.

Afghan National Security Forces

With the US committed to withdrawal from Afghanistan by the end of 2014, the ANSF will soon have to take over security responsibility for all of Afghanistan. Therefore, the development of the ANSF is of critical importance. The DoD report highlights the improvements in the ANSF. Both that report and the Congressional testimony of General John Allen, commander of ISAF forces, state that progress for ANSF has been “better than expected.”

The Afghan National Army has reached it end state goal of 195,000 troops, six months earlier than planned. The Afghan National Police has nearly reached its goal of 157,000. These are significant milestones, since training priority can now shift from growing the forces to improving their quality and technical capability. Personnel attrition rates, a major problem last year, have improved, according to the DoD. Literacy training has made substantial progress. The ANSF has filled its billet for officers, although there is still a shortage of non-commissioned officers.

Performance evaluations indicate that the quality of the ANSF is improving. Combat units have improved their ability to conduct operations with less and less support from ISAF forces. Government security ministries have made progress in developing the institutional capacity necessary to oversee, manage, and sustain the ANSF. The report particularly notes the Afghan National Army Special Forces, which has emerged as the most capable component of the ANSF and has made significant progress toward becoming an independent and effective force. In addition, the local defense initiatives Village Stability Operations (VSO) and Afghan Local Police (ALP) are proving to be a successful means for local villages to provide for their own defense.

On the other hand, the development of support and logistic functions has lagged. This is to be expected, since fielding fighting units was intentionally given a higher priority over support units. Also lagging, however, is the Air Force, which is technically the most challenging and complex service and suffers the most from lack of human capital. And the Afghan National Police continues to lag behind the Afghan National Army in creating an effective and less corrupt force.

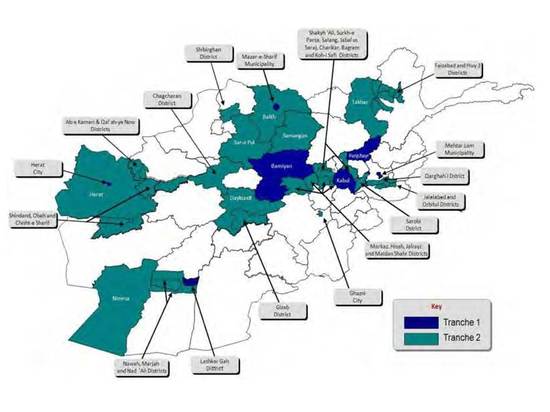

With increased capability, the ANSF has been taking over security responsibility for more areas. Since July 2011, large areas of the country have transitioned to ANSF, so that today, 50% of the Afghan population lives in areas of ANSF security responsibility. [See map below.] Thus far, the ANSF in the transitioned areas has performed adequately.

While the progress achieved is gratifying, there are also major risks. This is due largely to the fact that the ANSF has not yet been tested under heavy stress. So far, the areas transferred to ANSF responsibility have been the more benign ones, the areas less affected by the Taliban insurgency. The more difficult and dangerous areas will follow soon. By late 2012, 66% of Afghan population will likely be under ANSF responsibility, and including some of more problematic areas will be unavoidable.

Even more significant, the US and ISAF will conduct a major drawdown of their forces this summer. ANSF units partnered with US/ISAF combat forces will see them replaced with much smaller contingents of advisors. Then by mid-2013, US/ISAF will end all combat operations, transitioning them entirely to the ANSF. The speed of this transition is pushing the ANSF into the fore faster than US commanders would have preferred.

Taliban insurgency

According to the report, a number of ANSF and ISAF operations were executed over the winter in strategically important areas, significantly the insurgents’ capability.

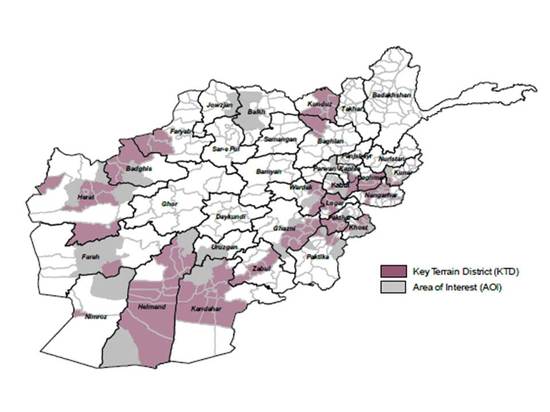

In southern Afghanistan, security has improved in Kandahar City and in the Arghandab River Valley to the west. This summer the insurgency will likely try to defend Maiwand district, as it is a strategic, logistical, financial, and support area. The insurgency will also try to regain influence in neighboring Zharay and Panjwai districts, west of Kandahar City. Currently about two-thirds of the insurgent attacks in southern Afghanistan are concentrated in the three districts.

In southwestern Afghanistan, the security situation has continued to improve in central and southern Helmand province. Insurgents have been pushed back to a few strongholds in northern Helmand. Operations are ongoing in Now Zad and Musa Qala districts.

In northern Afghanistan, security has improved dramatically, with insurgent attacks down 60%.

Eastern Afghanistan remains the most problematic area. The eastern border districts of Paktia, Paktika, and Khost provinces are the location of important border passes between the Taliban’s safe havens in Pakistan and Afghanistan. ANSF and ISAF personnel have conducted operations in these areas to improved security at border check points and along insurgent supply routes. These operations have decreased insurgent ability to refit and resupply for the coming summer fighting season, the DoD claimed.

The most vulnerable area is the insurgent infiltration route from Pakistan’s Kurram Agency into Afghanistan’s Logar and Wardak provinces. The route provides the insurgency with staging areas for attacks into the capital of Kabul. ANSF and ISAF operations have focused on limiting insurgent movements, disrupting insurgency activities, and forcing the Taliban to relocate command and control nodes, all of which, according to the report, has degraded the Taliban’s ability to conduct high-profile attacks in Kabul.

While these accomplishments cited in the report are extensive, it is too soon to say how effective they really are. They occurred during winter, which is the low season for insurgent activity due to the severity of the weather. The true indications will come this summer, when the Taliban will attempt to retake lost areas and step up attacks in Kabul and in provincial capitals. Then answers will come to the important questions that remain: Has Taliban capability been degraded significantly? Are the Afghan/ISAF gains sustainable, preventing the insurgency from mounting major operations over the summer or beyond?

The report states that a five-year trend of increasing insurgent attacks has been halted and reversed. For the first time, attacks were down, by 9% in 2011 and a further 16% so far in 2012. Decline is the right direction, but it should be noted that the decline is not large. It certainly is not large enough to indicate that the insurgency has been significantly degraded. Given the US and ISAF surge of forces over the last two years, and the fact the surge is coming to an end, the relatively small decline is underwhelming.

The report notes that opium production continues in southern Afghanistan. In fact, production is expected to increase by a small amount this year. Opium production has been and continues to be a major source of the Taliban’s income. The original purpose of sending such a large portion of the surge forces into Helmand province was specifically to cut this revenue stream. The fact that this goal has not been accomplished is a significant failure of the surge.

The most significant remaining risk is that the Taliban continue to receive critical support and sanctuary from safe havens in Pakistan. The Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI), Pakistan’s military intelligence agency, still supports the most effective of the Taliban organizations, the Haqqani Network. As long as the Taliban can rest and refit in the safety of Pakistan (and continue to receive revenue from opium production) there is little prospect for an insurgent strategic defeat. The best that can be realistically hoped for is a stalemate with fighting continuing for a long time to come.

Afghan governance

The performance of the Afghan government remains another major risk. The report states that the capacity and effectiveness of the government are undermined by widespread corruption, limited human capital, and concentrations of power within the judicial, legislative, and executive branches. These factors slow the reinforcement of security gains and threaten the legitimacy and long-term viability of the Afghan government.

The risk assessment

The real tests for the ANSF and the Afghan government will begin this summer. Risk starts to rise with the return of the summer fighting season, the drawdown of US troops, and the further transfers of security responsibility to the ANSF.

Longer term, risk will continue to increase in 2013 as the US ends combat operations and the ANSF picks up responsibility for more difficult and dangerous areas. It will increase further through 2014 as US and ISAF forces complete their withdrawal, the ANSF assumes responsibility for all of Afghanistan, and US oversight of the government and the monitoring of corruption becomes minimal. And risk will mount even higher after 2014, if a proposed plan to reduce the size of ANSF is implemented. The plan, put forward by the US, would cut the size of the ANSF by a third starting in 2015 in order to save costs. It is based on the assumption the Taliban insurgency will be in decline by then.

5 Comments

Who wins in Afghanistan? The side that wants to more. We have given them a chance for peace and stability. But the only ones who can sustain it are the Afghan people themselves.

The key iscontinuing to bash the brains out of the Haqqani network and the Taliban in general. The Haqqani’s have killed 500 Nato and US troops. But US and NATO have killed or captured 5,000 Haqqani fighters and commanders. But we need to do more. We need to increase our drone strikes despite Paki objections…and keep up the US led night raids despite Karzi’s whining. If we do this we can prvail in Afghanistan. This is the US military the most powerfull military in history, that is where we have the edge other militaries like the Brits and Russsians didn’t have!

good info

I’ll stick with Lt. Col. Daniel L. Davis’s Conclusions and Observations….

Seems to me he has/had ‘alot more to Lose’ than abunch of Scrambled Eggs, Stars and Polly-ticians..towing to keep there Retirement Benny’s.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/06/world/asia/army-colonel-challenges-pentagons-afghanistan-claims.html?_r=1&ref=world&pagewanted=all

http://armedforcesjournal.com/2012/02/8904030

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2012/02/11/world/asia/atwar-dereliction-documents.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/apr/14/afghan-war-whisleblower-daniel-davis?cat=world&type=article

As long as the Taliban look at US forces and Us bases as unwanted *outsiders* , they will have the support of many Afghans.

Now that the Chicago conference has pledged to continue support of Afghanistan after 2014, the next meeting to fix the cash details will occur at the Tokyo

conference.

So, where will the Taliban get their money from ?

From opium farming, production and sale.