The 15th issue of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s (AQAP) Inspire magazine, which was released online on May 14, features two pieces on Ibrahim al Qosi’s life with Osama bin Laden.

Qosi worked for bin Laden in a variety of roles from the early 1990s until Dec. 2001, when he fled the Battle of Tora Bora and was captured by Pakistani forces. He was then held at the detention facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from 2002 until July 2012, when he was transferred to his home country of Sudan. Just over two years later, in Dec. 2014, AQAP reintroduced Qosi as a senior al Qaeda figure. [See LWJ report, Ex-Guantanamo detainee now an al Qaeda leader in Yemen.]

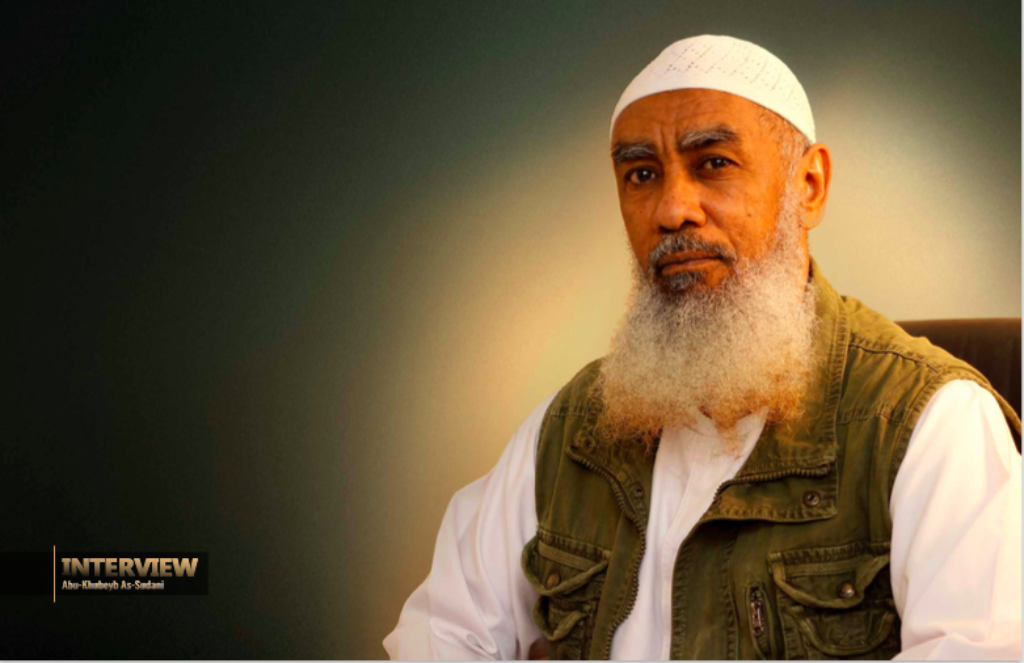

Qosi recounts his time with bin Laden in a lengthy interview with Inspire’s editors. The interview appears to be comprised partly of a transcript of Qosi’s answers to some questions one of his comrades posed and written text. For instance, the “interview” contains lengthy block quotes from books such as President Obama’s The Audacity of Hope. In addition to the interview, Qosi penned an article titled, “A Moment in the Life of Sheikh Usama,” which describes the financial difficulties al Qaeda faced around the time of the 1998 US Embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania.

As someone who worked closely with bin Laden, Qosi’s testimony provides another window into al Qaeda during its formative years, well before the 9/11 attacks changed the course of history.

The biographical details Qosi provides are consistent with those laid out in declassified and leaked files prepared by Joint Task Force Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO). [For more on Qosi’s background, see LWJ reports: Al Qaeda bodyguard and accountant pleads guilty before military commission and Bin Laden loyalist transferred from Guantanamo to Sudan.]

In his interview, Qosi explains that he sought to join the jihad against the Soviets in 1988, but he “met two brothers from al Qaeda, who came to Sudan from Afghanistan.” The pair of al Qaeda operatives “assigned…some commercial, administration [sic] and other activities” to Qosi in the Sudan. Only in August 1990 did he finally travel to Afghanistan. He was then “blessed” to “accompany and serve Sheikh Osama” from “the beginning of 1992 until our withdrawal from Tora Bora” and Qosi’s subsequent capture in Dec. 2001.

Al Qaeda in Chechnya

During that timeframe, Qosi was apart from bin Laden only from Aug. 1995 until July 1996, when he fought in Chechnya. Qosi says he fought first in the ranks of the Islamic Group (Gamaat Islamiyya), under the command of a jihadist known as Sheikh Fathi Abu Sayyaaf. After four months with the Islamic Group, which was closely allied with al Qaeda, he spent seven months “with Khattab.”

Ibn Khattab was the leader of the al Qaeda-backed Islamic International Brigade (IIB) in Chechnya before he was killed in 2002. Some have tried to distance the 1990s jihad in Chechnya from al Qaeda’s operations, but Qosi’s story is yet another indication of just how closely linked the two were. Qosi seamlessly transitioned from being at bin Laden’s side in Afghanistan to fighting as part of Khattab’s forces against the Russians in Chechnya and Dagestan. Indeed, the UN’s designation notice for the IIB documents the “[n]umerous ties” between al Qaeda and the jihad in Chechnya.

Al Qaeda in Somalia

Qosi also discusses al Qaeda’s early efforts in Somalia, saying the group’s “very first operations to hit America” occurred during the “fierce confrontation that took place between the Mujahideen and the Americans in 1993.” Qosi is referring to the infamous “Black Hawk Down” episode and the events surrounding it.

“It is worth mentioning that the brothers had thought of having a presence in Somalia since early 1992, before the arrival of the UN troops,” Qosi says. “This was because of its strategic location and many other reasons, on top of them was fighting the invaders.”

He continues: “So some brothers were sent to evaluate the situation and [enter into a] general relationship with the Islamic unity movement [al-Itihaad al-Islamiya],” which had a “strong foothold and presence on the ground.”

Al Qaeda was prepared for the UN troops who entered the East African country. “Before the deployment of the UN troops, al Qaeda had already mobilized all its military experts to train the Mujahideen in Somalia and the youth of the Islamic union movement,” Qosi says. “They taught them how to handle weapons, how to fight in the cities and how to use remote controlled IEDs [improvised explosive devices].”

According to Qosi, the “Mujahideen in Somalia and their brothers from al Qaeda…joined forces to battle the Americans.” Bin Laden’s former lieutenant explains that the “biggest blow for America…occurred at the port, where eighteen American soldiers were killed and there was the dragging of the American officer after targeting his Black Hawk helicopter by RPG [rocket propelled grenade].” He says the American withdrawal from Somalia was a “defeat” at the hands of the jihadists.

A defector who became “a gem that fell from the skies” for the Americans

Qosi also confirms just how damaging one of al Qaeda’s earliest defectors was to the jihadists’ cause. In the mid-1990s, an al Qaeda operative named Jamal al Fadl embezzled funds that were intended to serve bin Laden’s cause. After being found out, Qosi says, Fadl fled and sought “refuge in the American embassy in Eritrea, telling them that he was a member of Al Qaeda and he was close to Sheikh Osama.”

Fadl “informed” the Americans “that he had valuable information on the activities of al Qaeda against the interests of America in East Africa, Sudan, Somalia, Yemen” and elsewhere, Qosi recalls. Fadl “was a gem that fell from the skies in the hands of the Americans.” In fact, Fadl became one of the US government’s star witnesses during the 2001 trial of some of the terrorists responsible for the 1998 US Embassy bombings.

Qosi says that Fadl’s defection was the “first time” the Americans got ahold of “inside information on the economic and military activities of al Qaeda in the area,” leading to the capture of “our brothers.” Among those detained was al Qaeda leader known as Abu Hajir al Iraqi, who is still imprisoned inside the US.

Qosi also blames Fadl for bin Laden’s expulsion from Sudan in 1996. “With this information in hand, the American government pressured the Sudanese government to surrender Sheikh Osama or expel him out of Sudan,” Qosi says. “Sudan refused to surrender him [bin Laden] and opted to expel him.” The Sudanese “planned in secrecy without” bin Laden’s “knowledge” to “send him to Afghanistan after contacting some of the jihadi leaders in Jalalabad who welcomed the idea and waited to receive him.”

“One night,” Qosi explains, the vice president of Sudan at the time, Omar Bashir, “knocked on the Sheikh’s [bin Laden’s] door.” Bashir explained to bin Laden that “there had been immense pressure on them to expel him from Sudan” and that the Sudanese government “had arranged and planned for him [bin Laden] to travel to Afghanistan and be a guest among the leaders of jihad in Jalalabad.” One of the jihadi leaders willing to receive bin Laden was Sheikh Yunus Khalis, a veteran of the 1980s war in Afghanistan who died in 2006. Qosi praises Khalis, Taliban founder Mullah Omar, and another jihadist commander, Mullah Dadullah, for their steadfast support for bin Laden in Afghanistan.

Sudan was an ideal staging ground for jihad until Fadl’s betrayal, according to Qosi. Bin Laden’s man claims Fadl gave American authorities “false information about Sheikh Osama’s role in” bombings that were carried out in the mid-1990s, including in Riyadh and at the Khobar Towers. (The latter attack, which left 19 US servicemen dead in 1996, is a known Iranian and Hezbollah operation. But it has long been suspected that al Qaeda played a role as well.) Still, Fadl gave the US “loads of information regarding every mujahid he ever knew.”

Striking America and building an Islamic state

Qosi also discusses why bin Laden and al Qaeda came to view America as their primary target in the years leading up to 9/11. Attacking the US was viewed as a necessary step toward their real goal of building an Islamic state. Qosi says that bin Laden believed it would be pointless to have the jihadists “separated with different tasks by fighting of their respective apostate governments” throughout the Muslim majority world.

The al Qaeda master believed that the jihadists could not “establish an Islamic state until” America experienced a “total meltdown,” Qosi says. Only if America “falls,” then “the regimes it backs” would “fall too.” America “alters and shifts any government that tries to implement the Islamic law,” Qosi complains, because it seeks to impose the “values of democracy and secularism through regimes and governments working as agents and allies.” In addition, the US “aids the Jews militarily” and “economically,” as well as providing them with “security and spiritual support.” For all of these reasons, Qosi says, bin Laden believed that America should be in the jihadists’ crosshairs first.

Qosi’s remarks focus on bin Laden’s thinking before the 9/11 attacks. Al Qaeda’s strategic calculus has changed throughout the years, especially after the Arab uprisings in 2011, when several dictators felt their grip on power slip. Al Qaeda has made the “local” insurgencies in Syria, Yemen and elsewhere a priority, as the group now believes that there is a greater potential for raising Islamic emirates in these locales.

Qosi offers some words in remembrance of the 9/11 hijackers, including the leader of the suicide squadron, Muhammad Atta. Atta “was always at the service of his brothers,” helping in the kitchen, Qosi reminisces. Atta was always “among the first in prayers.”

As one of bin Laden’s most trusted subordinates during the 1990s, Qosi’s testimony is being used to connect a new generation of jihadists with al Qaeda’s past. He has played an increasingly significant role in AQAP’s propaganda since late last year and he will undoubtedly continue to do so, as long as he survives the drones buzzing overhead.

3 Comments

I always thought the primary motive for 9/11/2001, was that Osama Bin Laden couldn’t tolerate the insult of Americans sending women soldiers to Saudi Arabia during Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm in the 1990/1991 timeframe. Seeing women, possibly wearing shorts, walking around unescorted in the shadows of mosques in Saudi Arabia was apparently too much for Osama to tolerate, and that’s when he went off the deep end.

Thanks for a fascinating article detailing some of the inside thinking within AQ.

[A]s long as he survives the drones buzzing overhead.

Indeed. He’s definitely been added to the CIA’s kill list. 🙂